Concept

Analysis of data usually involves putting data into a more easily accessible format (visualization, tabulation, or quantification of qualitative data).

By Taormina Lepore

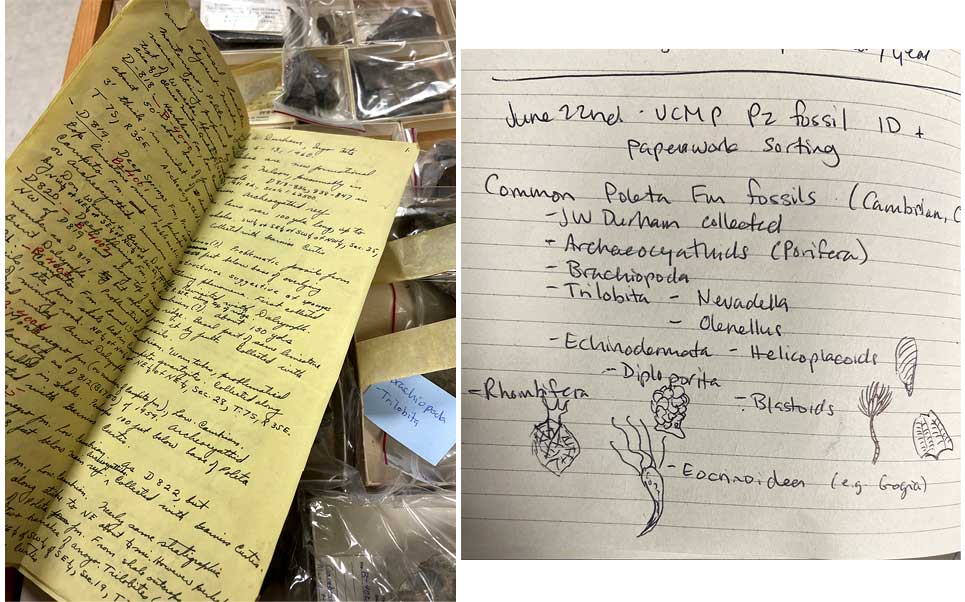

Image Source: Taormina Lepore

Identifying fossils can be like figuring out what an entire jigsaw puzzle looks like, based on just one or two pieces, when the box cover and the other pieces are missing. Often scientists only find pieces of fossils, so they don’t have the full picture at hand. But they can better understand the evidence available to them by creating visualizations of fossil data, such as illustrations of organism shape and form. This puts the data into an accessible format that scientists can keep track of and add to as they build their understanding of the natural world.

Ideally, paleontologists who are very familiar with a particular organism will be able to identify fossils as they are collected. But other times, especially in years gone by, fossil collectors simply picked up as many fossils as they could, without keeping a very strong paper trail of the fossil’s possible identity. Such practices can lead to drawers full of mismatched, unidentified fossils – a jumble of pieces from different puzzles.

At the University of California Museum of Paleontology, some of the fossils are still in limbo like this – notably those in a few cabinets that were collected by JW Durham and his students between the 1950s and the 1980s from the Poleta Formation in the western United States. Durham picked up thousands of fossils – he truly had an excitement and passion for his work – and many of these lack a label noting their species.

While digging through the wooden drawers in these mystery cabinets, graduate student workers and museum staff noticed pieces of paperwork tucked among the fossils. These contained detailed notes from Durham on some of the fossils from a Poleta Formation expedition – more clues that today’s paleontologists are using to help piece together the fossil identities.

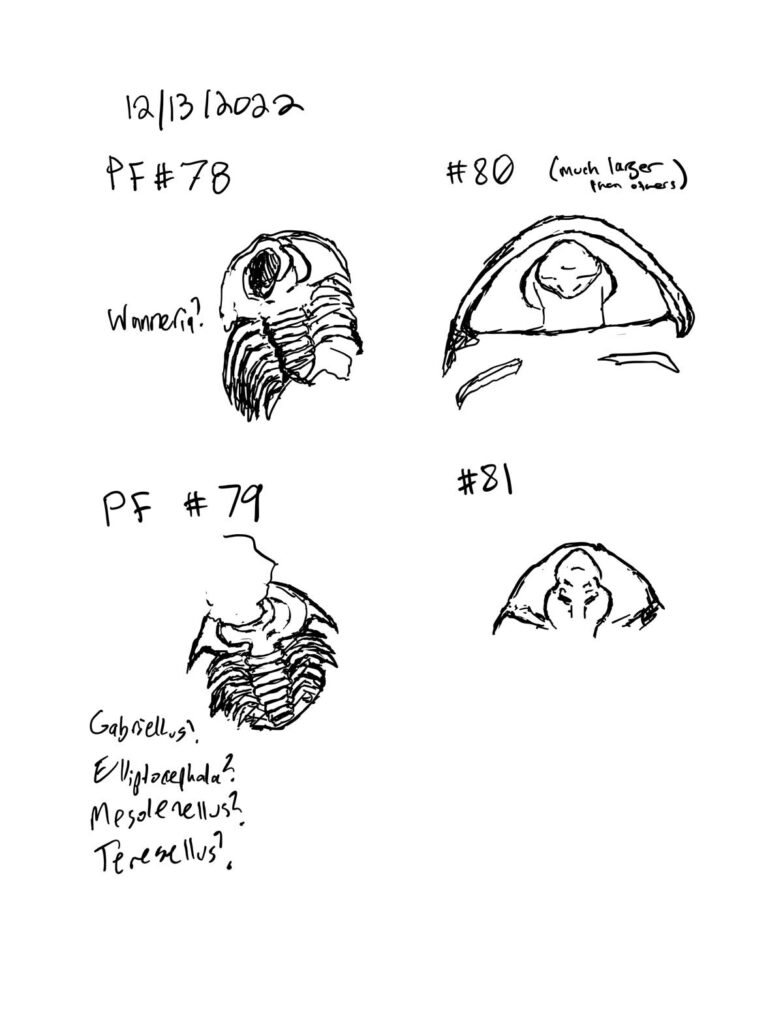

In addition to reviewing Durham’s notes, museum graduate students made their own drawings based on the shape and form of the incognito fossils, as well as the published anatomy of different fossil groups. For example, graduate student Tanner Frank made anatomical drawings to identify the genus name of several trilobites – ocean-dwelling cousins of horseshoe crabs.

Visualizing data about the fossils in this way makes the information easier to access and analyze. Museum curators can then enter all the new information about the fossils into a database, which can be easily sorted and tabulated.

This whole process of visualizing and tabulating data on fossils gives emerging scientists the opportunity to practice fossil identification skills and helps museums build a more accurate assessment of the fossil specimens they have. It also makes the fossil data easier to analyze and share with other scientists, helping them solve their own fossil jigsaw puzzles as they build new knowledge about ancient life.